Feb 12

One thing was immediately noticeable as I stepped off of the plane: the smell of smoke, hanging thickly in the air. Later, I would discover that it was the smell of burnt trash, but at that time, my only thought was, “Finally. Rwanda.”

I found out about the Investigative Journalism Adventure to Rwanda last summer and immediately committed myself to the trip. During all of first semester this year, I researched how the country led itself to the point of mass murder.

It didn’t hit me until I was standing in LAX at 5:30 a.m. on Friday, Jan. 24. that I was going to Rwanda, a country I had only heard about once or twice in the news prior to the trip.

I realized that even though I knew much about the country’s torn past, I knew nothing of its current situation.

My dad’s safety briefing, minutes before we separated — always walk around with a buddy, check in with an adult every night, don’t eat things that strange people give you, if you get lost, call the United States Embassy — did nothing to ease my nerves.

The minute we arrived in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, we were met with stares. We were a group of 18 tired Americans in the single-terminal airport, 10,000 miles from home.

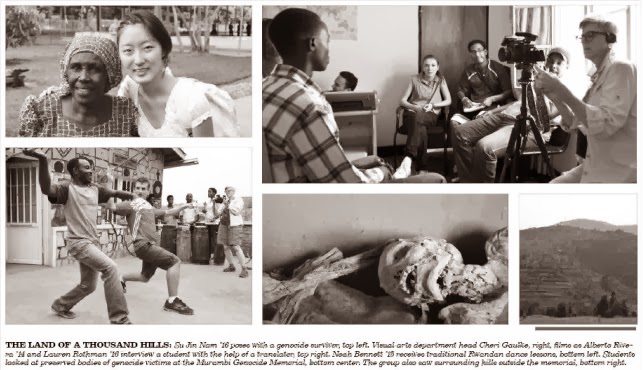

In the morning, we caught our first glimpse of Rwanda. The sprawling hills provided the same breathtaking view everywhere in the country. Rwanda’s second name, “The Land of a Thousand Hills,” was definitely not a misnomer.

We saw the culture and lifestyle of the Rwandan people whizzing by as we traveled on the bus. I saw people carrying water to their homes and women carrying babies on their backs, a basket on their head. We began to wave at the Rwandan people, and most made a welcoming gesture back at us.

Much of the anxiety I felt about going to a recently violent country fell away.

These people were happy and open. They weren’t the hostile and closed-off culture I had imagined that they would be. I was beginning to feel accepted by these people.

Before the trip, each of the students chose a specific topic they wanted to focus on during and in the follow-up activities after the trip. Some compared the Rwandan genocide to the Holocaust, others focused on the children in Rwanda and one group brought soccer balls to distribute and document how the sport was helping the country heal. I decided to turn my attention to the women of Rwanda and what they were doing to heal their country and shape its future.

As I walked through the exhibit on the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsis in the Kigali Genocide Memorial, I was hit by the magnitude of the killing.

I realized the pictures and descriptions I had come across in America did not even begin to capture the true nature of the genocide. When I came across a certain line of text in one of the descriptions, I sat against the opposite wall, staring at it, reading it over and over again until I couldn’t bear to look at and imagine it any longer. Even when we exited the memorial and got on the bus to go to our next destination, the line wouldn’t stop flashing in my mind as I closed my eyes and rested my head against the window.

Hutu and Tutsi women were often forced to kill their own Tutsi children.

Later that day we ran into a crowd of children in a village. They smiled and pointed at us. When they came closer, we took pictures with them and taught them how to use our cameras. It was then that I first saw the effects of the healing process with my own eyes, the happiness and acceptance of the new generation.

At the Learning Center, an institution that provides English, music and computer classes for Rwandan youth, we met Kizito, a survivor, who watched his mother get raped and his siblings being burned alive in his house when he was a child.

His mother and brother survived the genocide, but his mother is now bed-ridden with HIV.

He traveled with us for most of our trip, and everyday it amazed me how he could look so happy, smiling and laughing with us, even with his painful past.

We visited other survivors who were willing to relive the pain and share their stories.

One woman said that she prayed every night for God to forgive her and to watch over her attackers. I was dumbstruck by her ability to pardon those who had wanted to kill her. Her prosthetic eye rested on me as she said, “Thank you for coming to learn.”

Another survivor’s story was truly heartbreaking. At 82 years old, she had survived two major genocides in 1959 and 1994.

All of her six children were killed, and she lives with one grandchild. She remembers having lost at least 1,000 people in both genocides, all of whom she knew by name.

What affected me most from her story was the fate of one of her daughters. The woman’s daughter was a Tutsi who married a Hutu man before the genocide. Together, they had a mixed child. When the genocide began, the Hutu son-in-law killed the Tutsi daughter and grandchild. The son-in-law has recently been released from prison and taunts the woman in the streets of her village.

One of the most uncensored genocide memorials made it apparent to me that, under the healing, the scars still remain.

Murambi Genocide Memorial is a picturesque university that never opened and now showcases the preserved bodies of victims killed there. In the bodies laid down side by side, I could see the wounds, the machete cuts and the forms these people were in as they died. Some have their arms above their face, blocking their attacker even in death. Seeing these bodies was the final step in my realizing the sheer brutality of this genocide, merely 20 years ago.

On the way to Musanze, where we would go gorilla trekking, we visited a school for the deaf. Even though they couldn’t hear the music, they danced to our laughter. As we blew balloons and bubbles, they looked happy. I recalled something that each survivor had been telling us throughout our trip. Education is the way to prevent a future genocide and provide a hopeful future for Rwanda through its younger generation.

The last night yielded a spectacular lightning storm less than five miles away. The sky lit up an electric purple as the night wind blew around us. We watched from the hotel balcony as the thunder boomed.

It was another experience that was purely Rwandan, something I couldn’t witness back home in Los Angeles.

The day we went gorilla trekking, we woke up at 4:30 a.m. The hike through the Rwandan jungle was harsh, and the plants and insects foreign. But the first glimpse of the silverback gorilla made up for all the fears and worries.

The animals were not even five feet away. A baby with a missing foot came closer, and at one point he emptied his bladder on himself. Adolescents in the troop were playing, a mother was cradling her baby and the silverback was napping. It was amazing seeing these creatures who are genetically similar to us in their natural habitat. I had the feeling of being welcomed into their home as we observed them. I reflected back on my time in Rwanda, all the things I experienced and the new world view I had obtained on the hike back down the mountain. I was surprised by how much I had changed in the course of 10 days.

The bus ride back to Kigali was rushed, the possibility of missing our flight hanging over our heads. We arrived at Kigali International Airport, back where our adventure in Rwanda began, on time to make our flight. As I took one last photograph of the airport, I came to the conclusion of the thought process that I had begun on the hike down the mountain.

Somewhere along my journey, I fell in love with this country.

Rwanda and its culture accepted and changed the unlearned me into a cosmopolitan human being.

Someday I wish to go back, experience more of the culture and help make the country’s goal of “never again” a reality.

Harvard-Westlake Chronicle